Research

For more than a century, SickKids has been synonymous with research excellence.

While our commitment to advancing patient care through cutting-edge research is ongoing, these highlights offer a glimpse into the countless care providers and researchers who are bringing scientific discoveries from the lab bench to the bedside, and transforming care for children everywhere.

From hospital to research powerhouse

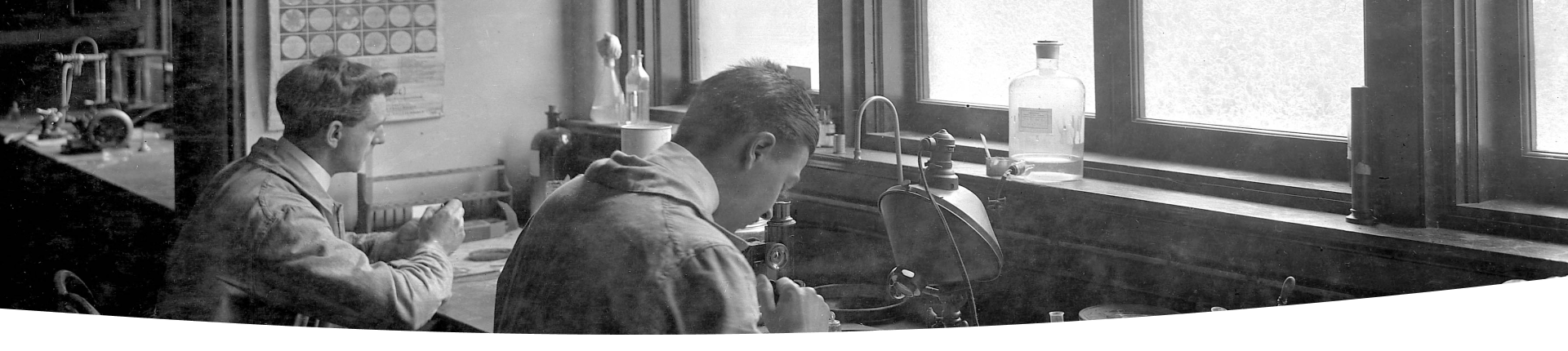

SickKids has always sought to use the latest evidence, tools and knowledge to improve care—but our Research Institute wasn’t officially founded until 79 years after the hospital opened. So how did research take root, grow and evolve into the thriving institute it is today?

Organized research began at SickKids in 1919 by Dr. Alan Brown and shortly afterwards in 1920 his colleague, Angelia Courtney, came to Toronto as the first Director of the hospital’s new Chemical Research Laboratories.

The infant cereal Pablum was first developed in the early 1930s by Drs. Alan Brown, Theodore Drake, and Frederick Tisdall*. The cereal was designed to be mixed with breast milk or formula to create an easy-to-digest and nutrient-rich food for infants.

In 1954, the Research Institute was officially established with proceeds of the Pablum patent and generous support from estate of J.P. Bickell. It has become the largest hospital-based research facility in Canada and one of the largest in the world.

*SickKids acknowledges harmful aspects of the hospital's history with Indigenous people. Between 1942 and 1952, on behalf of the Department of Indian Affairs of Canada, Dr. Frederick Tisdall and his team conducted nutritional experiments on malnourished populations in some Indigenous communities and residential schools. We are committed to acknowledging and addressing the legacy of this research.

Advancing genomic breakthroughs

SickKids is a powerhouse in genomic research, with a legacy that has driven global discovery and spurred new therapies. In the 1980s, SickKids teams led a number of advancements in genomics, from the identification of variations in the RB1 gene in retinoblastoma patients led by Dr. Brenda Gallie in 1988 to Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui’s breakthrough discovery of the gene responsible for cystic fibrosis in 1989. Today, Dr. Stephen Scherer’s research on copy-number variants (CNVs) has since been implicated in a number of conditions, while Dr. Julia Upton’s first description of a new genetic cause of allergy in 2022 may provide a path to reducing the impact of devastating allergies.

The gene responsible for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the most common neuromuscular genetic condition, was uncovered by Dr. Ronald Worton in 1986.

Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui, along with his team including Drs. John (Jack) Riordan, Manuel Buchwald and Johanna Rommens, discovered the gene responsible for cystic fibrosis in 1989.

Dr. Diane Cox (left) discovered the gene responsible for Wilson disease in 1993. Dr. Margaret (Peggy) Thompson co-authored Genetics in Medicine, the world's leading genetics textbook which continues to be used today, in 1966.

Dr. Stephen Scherer identified large-scale CNVs across the genome in 2004, changing our understanding of the genomic architecture of autism spectrum disorder — work that researchers like Dr. Ryan Yuen in the Genetics & Genome Biology program continue to advance.

From early diagnosis to improved cancer treatment

Cutting-edge cancer treatment is a cornerstone of care at the hospital, with innovations driven by SickKids labs shaping the practice of oncology. From the identification of leukemia stems cells by Dr. John Dick in 1994, to the first prospective identification of cancer stem cells in human brain tumours by Dr. Peter Dirks in 2004, which transformed our understanding of solid tumour growth, SickKids has been at the forefront of cancer research. As basic research in cancer biology accelerated, so did clinical research to enhance patient monitoring and care. In 2011, led by Dr. David Malkin, the Toronto Protocol influenced cancer screening and early detection for patients with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), increasing survival rates for patients with the condition. Most recently, a 2024 study by Dr. Sumit Gupta found blinatumomab immunotherapy improved outcomes for children with newly diagnosed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), the most common childhood cancer.

In 1994, Dr. John Dick was the first to identify leukemia stem cells while working at SickKids, revealing a hierarchy within cancer cells and laying the groundwork for future therapies for the condition.

Juliet Locke, pictured here with Dr. David Malkin, and her family participated in clinical trials at SickKids and UHN that helped to establish the Toronto Protocol, as well as later research showing the benefits of adding liquid biopsy for patients with LFS in 2023.

Santiago Reyes was one of 1,400 children newly diagnosed with B-ALL to participate in the global clinical trial co-led by SickKids.

Research with global impact

SickKids is dedicated to improving the health of children around the world. In 2002, Dr. Stanley Zlotkin, the Inaugural Chief of the SickKids Centre for Global Child Health, invented Sprinkles, a micronutrient powder distributed to millions of children worldwide to address malnutrition. Similar initiatives to address global health inequities and challenges are found throughout the Research Institute, including from Dr. Jean-Philippe Julien who is investigating interventions that prevent the transmission of malaria.

Sprinkles, which was first piloted in Haiti in 2002, contains a blend of essential vitamins and minerals, including iron, zinc and vitamin A.

Dr. Jean-Philippe Julien invented the Multabody, a unique technology that can combine antibodies into a single-molecule drug and spurred the spinout company Radiant Biotherapeutics, with support from SickKids Industry Partnerships & Commercialization.

The talent behind the discoveries

SickKids is home to some of the most talented clinicians and researchers in the world. Many of them started as trainees, while others came from farther away to lend their expertise to advancing child health research.

In the 1992 edition of Kaleidoscope, a magazine that used to be published by SickKids, six female SickKids scientists spoke about breaking ground in research. Drs. Julie Forman-Kay and Lynne Howell (both shown on the cover), Jayne Danska, Daniela Rotin, Cindy Guidos and Christine Bear continue to conduct their research at SickKids to this day.

The future is Precision Child Health

Exciting new research is being conducted every day at SickKids, and discoveries like those made by Dr. Sheena Josselyn, whose 2007 description of memory engrams has revolutionized the field of neuroscience, are what continue to set us apart. Amongst all this success is a compelling driving force: Precision Child Health. With the opening of the Peter Gilgan Centre for Research and Learning (PGCRL) in 2013, collaboration and partnership are informing a new era of health research — one centred on tailoring care to the individual needs of every child, from the genetic code to the postal code, and driven by research. From the first single-patient clinical trial at SickKids for spastic paraplegia type 50 (SPG50), to sequencing patient genomes to connect genetics with the social determinants of health, the future of SickKids research will support individualized care for every patient and their family.

The PGCRL opened in 2013, bringing once disparate research labs together in a single space with specialized equipment and facilities like The Centre for Applied Genomics that are advancing cutting-edge research.

Michael Pirovolakis received the first gene therapy in a single-patient clinical trial at SickKids in 2022 for his ultra-rare genetic condition (SPG50), delivered by Dr. James Dowling, marking a major milestone for the future of Precision Child Health.

Drs. Jennifer Crosbie and Russell Schachar partnered with “junior scientists” at the Ontario Science Centre to collect population spit samples in a community-based space and explore how genes and the environment interact to shape children’s physical health and mental well-being.

Want to learn more about SickKids research history?

Check out our growing collection of artifacts that shine a light on the history of medical research at SickKids.