SickKids’ VAD program is giving hope to patients with heart failure

Summary:

The only paediatric Ventricular Assist Device program in Ontario empowers patients with heart failure and their families, in and out of the hospital.

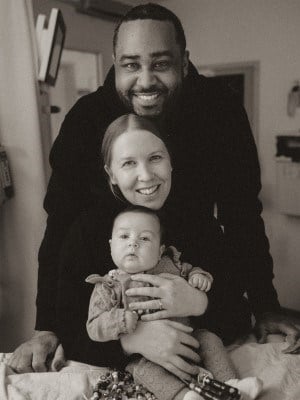

Sloane Atkinson was a chatty, alert baby, just six-and-a-half weeks old, when her parents noticed one day in December she stopped eating, became fussy and developed blue colouring around her mouth. They thought they were being overly worried first-time parents, but at a B.C. hospital, they learned Sloane’s heart was barely beating.

It was like “a bomb being dropped,” her mom Stephanie Mulhall-Atkinson recalls.

Sloane was diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy, later found to be caused by a gene variant she didn’t inherit from either parent. The left side of her heart wasn’t pumping enough to circulate blood through her body; the right side had compensated when she was born, allowing her to grow and initially appear healthy. She was intubated and in a fragile state.

After around two weeks, doctors told her parents that Sloane’s heart likely wouldn’t recover on its own and she would need a transplant to survive and, in the meantime, options were limited.

A 15-minute conversation with a transplant doctor at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) changed everything, Stephanie says. SickKids has an established program for the heart pump device that could help Sloane, called a Ventricular Assist Device (VAD), and a history of excellent outcomes for using VADs to bridge an infant to transplant.

“By the end of it, we were like, ‘OK, we’re 100 per cent coming, there’s no thought about it,’” Stephanie says.

We feel really happy and hopeful that she’ll be OK.

In less than 24 hours, everything was in place. Two days later, Stephanie, her husband Justin, and Sloane were on their way to SickKids. Within a week, she was booked for VAD surgery. She had a rough recovery from all of the medications she was on, but Stephanie describes feeling a “different level of hope” once Sloane was on the VAD.

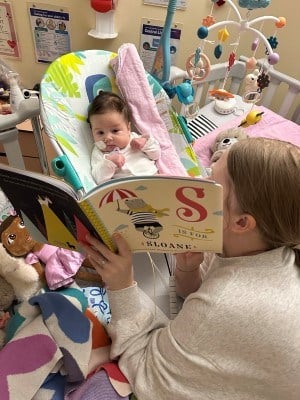

Now, four-month-old Sloane has tubes surgically implanted into her heart that come out of her chest and carry blood back and forth, connecting to a pump that sits outside her body. With the device doing the work of her heart, and the medications having worn off, she’s growing and getting stronger by the day.

The device and care have caused “a complete shift.” Sloane’s “feisty” personality is back — she’s relearning how to use her bottle, curiously watches her nurses and doctors and is very chatty.

“We feel so hopeful, even though it’s such a dramatic thing that our baby needs a heart transplant and that’s not something we would ever imagine would happen,” Stephanie says. “We feel really happy and hopeful that she’ll be OK.”

A Canadian leader in paediatric VAD usage

SickKids Cardiologist Dr. Aamir Jeewa has an encouraging message when he talks to families of patients who need a VAD: “Every day is going to get a little better."

Families often have a lot of fears in the beginning of the process, says Jeewa. He recognizes their anxieties are reasonable: The surgery to implant the heart pump is a big one, and the first month after the surgery is hard — but patients progress and get stronger from there.

Jeewa, who is the medical director of SickKids’ VAD program, points to the program’s positive results: Since SickKids’ VAD program launched in 2004, about 90 per cent of patients put on a device went on to either recover their heart function or, more commonly, receive a heart transplant.

“That shows that this is an additional tool for treating end-stage heart failure in paediatric patients,” he says.

Heart month decorations in SickKids' Cardiology unit.

SickKids has the only paediatric VAD program in Ontario and one of three in Canada. Approximately four to seven children need a VAD each year. Some have devices like Sloane’s that are outside the body; older patients can have the device implanted inside their chest, which allows them to return home.

Jeewa says the interdisciplinary team is always trying to find ways to improve patients’ quality of life, including through research and using Precision Child Health principles to detect heart failure symptoms before they develop and tailor appropriate medication and therapies to patients.

In addition to using VAD to recover heart function or bridge to transplant, SickKids also uses the devices intermittently to support very sick patients — such as those in cardiogenic shock or acute heart failure — or longer-term to help clinical teams decide the best course of action for a patient.

Whether it’s a short- or long-term use of the device, education is a big piece of SickKids’ program.

“We always try to sit down with families and prep them before their child goes in for a VAD. It’s very much a team effort,” says VAD program coordinator Andrea Maurich.

Learning a child needs a VAD can completely alter a family’s lives, she says, and can be especially overwhelming when a child seems otherwise healthy and then becomes very sick and needs the device.

“They have a lot of questions, and whatever we can do to make the whole process easier on them is what we do.”

'A sense of relief'

When Stephanie and Justin first learned about VAD, they had no idea what it was — “it felt like something that never happens,” Stephanie says. But their initial conversation with the SickKids team gave them hope, and they’ve become more confident watching and learning from the VAD team.

“Having a team dedicated just to her VAD is so major,” Stephanie says. “The biggest thing for us is seeing how confident, how knowledgeable, how skilled they are, how they’ve perfected the whole system and how they work together and work with us too.”

“There’s a process they go through that keeps you so well-informed, you become knowledgeable in everything and it gives you a sense of relief knowing she’s in literally the best hands and they’re going to take care of her from there, and they constantly check in on you,” Justin echoes.

Although Sloane has to remain in hospital until a transplant, the family’s days are similar to what they’d be like if they were at home. If you didn’t notice Sloane’s VAD, she’d look like any other baby, Stephanie says.

“Now that she’s not intubated and she’s healthy, we get to care for her like we would if we were home. We get to pick her up whenever we want, and we can fully care for her,” she says.

The VAD has given them more independence — they go on walks around the hospital, visit the multisensory room and walk down to the cafeteria to eat or get coffee. Now that Stephanie and Justin have been trained on the device, they can bring Sloane around the hospital without relying on a VAD-trained nurse to accompany them. On a recent walk, they ran into the team who cared for Sloane in the Cardiac Critical Care Unit and they got to see how, seven weeks after the VAD surgery, she’s so much bigger, happier and healthier.

They’ve also talked to another family in a similar situation. Stephanie says she wants other families to know while learning their baby needs a transplant or a VAD might feel hopeless, the hospital’s program is a reason to have hope.

“Although it’s the worst day of your life, there is this light at the end of it, knowing that there is something that can bridge her to transplant.”

When he learned he was going to get a VAD, 12-year-old Harrison asked a question Maurich, the program coordinator, had never heard before: Can I ride a rollercoaster with it?

The answer, unfortunately, is no — but with the device inside his body and connected by electrical cords to a controller and batteries he carries in a backpack, Harrison was able to be discharged home two-and-a-half weeks after his recent surgery. His device is an LVAD to pump blood to and from the left side of his heart, allowing the organ to get stronger after he was admitted to SickKids in early January and diagnosed with cardiomyopathy.

Harrison was born with a congenital heart defect and had surgery as a newborn. He was followed by SickKids through regular appointments, but everything seemed to be looking good, says his mom, Tiziana. His parents thought he had a stomach virus when he was feeling sick in early January — so to learn he was experiencing heart failure and would need a VAD was “very much out of left field.”

The surgeon who did his original surgery 12 years ago had requested to perform his VAD surgery, something Harrison’s parents found comforting. While admitted, Harrison enjoyed seeing the therapy dogs, playing video games and doing crafts in Marnie’s Lounge. Staff always made Harrison feel comfortable, Tiziana says. His stuffed capybara was a point of conversation with new nurses, and one even found capybara stickers for him. Nurses were also great at coaching him on pain management, ensuring he’d tell them when he felt pain. The team explained everything that was happening, and Harrison was invited to rounds to listen to the team talk about his care.

There’s always a sense of really feeling like we’re being taken care of when we’re at SickKids.

“We absorbed so much information, but every step of the way people have been so sure to explain it to us. We were never left in the dark or at the mercy of their knowledge and us needing it translated. That meant a lot in terms of knowing what was going on and feeling comfortable with it,” Tiziana says.

“It's huge because you feel like you’re at such a loss. Normally you are used to being the ones who do everything you can do for your kid. It is difficult as a parent to not be able to make it all better for your child. So it meant a lot to be as included as much as we were.”

On his discharge day, Harrison’s family received a pleasant surprise: the VAD team, Cardiology nurses and Harrison’s physiotherapist lined the hallway to clap as they walked out of the unit to leave the hospital.

“It was really, really sweet,” Tiziana says. “There’s always a sense of really feeling like we’re being taken care of when we’re at SickKids."

After a few weeks at home, Harrison is already building up his energy and strength. He says he’s happy to be home because he can spend time with his dog Raven, play video games and sleep in his own bed. Although it sometimes bothers him having to remember to carry the backpack with his VAD items when he’s comfortable and going about his day, he’s adjusting to his new routine: changing his VAD from wall power to battery power in the morning, taking medication and doing physio.

Harrison also recently returned to school. Maurich and other members of the team help to coordinate with schools, as well as community partners like emergency services, to ensure staff are educated about VAD. Tiziana says as a parent, it was a bit nerve-wracking for him to go back to school, almost like the feeling she had when he started Junior Kindergarten. But staff at his school did a “wonderful job” making sure Harrison felt ready, and he was excited to be back with his friends and go outside at recess.

“His smile after school today really reminded us how blessed we are that he’s home and able to go about his regular routine as much as possible.”