Our earliest memories may be forgotten but not lost

Summary:

A new study from SickKids shows that early memories in mice are not missing and can be brought back by directly stimulating different clusters of neurons that represent individual infantile memories in the brain.

TORONTO - When asked to think of their earliest memory, most would think of a time when they were four or five years old. The period from birth to Kindergarten appears to be forgotten. Since the late 1800s, this phenomenon has been called “infantile amnesia” and debate on why we can’t remember our earliest years has persisted to this day: Are these memories gone or are they just difficult to access?

A new study from The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) shows these early memories in mice are not missing and can be brought back by directly stimulating different clusters of neurons that represent individual infantile memories in the brain. The results, published in Current Biology, provide deeper insight into the complexities of forgetting.

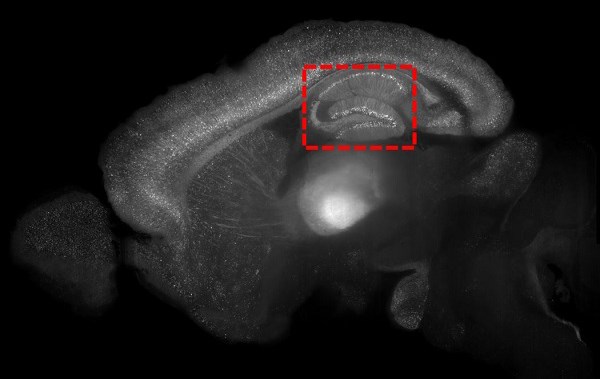

Dr. Paul Frankland, Senior Scientist in Neurosciences & Mental Health at the SickKids Research Institute, and his team trained infant mice to associate a specific place with a particular memory. This training engages the hippocampus, which plays a role in processing memories tied to a particular situation or context. The resulting memory of the place was forgotten within approximately one week.

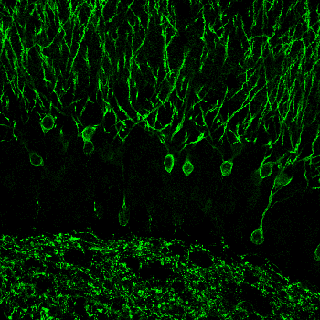

Next, they conducted the training again with different mice but this time they identified and tagged the specific neurons that were active in the hippocampus to keep track of them for the next phase of the study. Weeks later, when the place had long been forgotten, the researchers stimulated the tagged clusters and found the mice behaved as if they recognized the place once again.

“The memory recall was remarkable,” says Frankland, who is also an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Toronto. “These results suggest our earliest experiences are not completely forgotten or erased from the brain. Instead, we can bring them back through direct stimulation.”

The team used a precise method called optogenetics to selectively stimulate the clusters of neurons that corresponded with the infantile memory. When the researchers tagged the relevant clusters of neurons during training, they inserted a gene to make them responsive to light. Then, the researchers activated the tagged neurons by delivering light into the brain.

“The optogenetic strategy we used was crucial to achieve the level of precision needed to test whether we could bring these memories back,” explains Frankland. “We were able to target specific clusters of neurons for specific periods of time to recreate very specific memories.”

The study’s results point to retrieval failure – difficulty with accessing memories – as only part of the problems contributing to infantile amnesia. Although the adult mice showed evidence of remembering early memories with direct stimulation, the recovery was incomplete, indicating there may be problems with storing these early memories as well. These findings give greater insight into how the brain stores and forgets memories.

This research was supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR), the Human Frontiers Science Program (HFSP), the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Enterprise and the SickKids Foundation. It is an example of how SickKids is making Ontario healthier, wealthier and smarter (www.healthierwealthiersmarter.ca).

About The Hospital for Sick Children

The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) is recognized as one of the world’s foremost paediatric health-care institutions and is Canada’s leading centre dedicated to advancing children’s health through the integration of patient care, research and education. Founded in 1875 and affiliated with the University of Toronto, SickKids is one of Canada’s most research-intensive hospitals and has generated discoveries that have helped children globally. Its mission is to provide the best in complex and specialized child and family-centered care; pioneer scientific and clinical advancements; share expertise; foster an academic environment that nurtures health-care professionals; and champion an accessible, comprehensive and sustainable child health system. SickKids is proud of its vision for Healthier children. A Better World. For more information, please visit www.sickkids.ca. Follow us on Twitter (@SickKidsNews) and Instagram (@SickKidsToronto)

Media contact:

Jessamine Luck

The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids)

416-813-7654 ext. 201436

jessamine.luck@sickkids.ca